On Political Fetishism

The deceptively simple reward learning dynamic underlying our pervasive partisan brainrot

The territory no longer precedes the map, nor survives it. Henceforth, it is the map that precedes the territory - precession of simulacra - it is the map that engenders the territory and if we were to revive the fable today, it would be the territory whose shreds are slowly rotting across the map.

- Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation

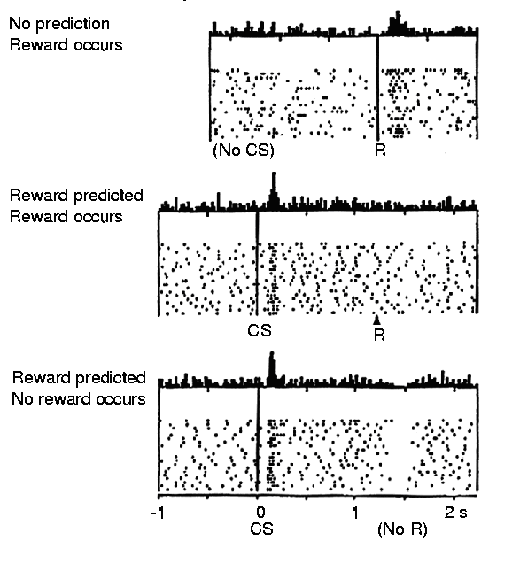

If you put electrodes into a monkey’s midbrain and subsequently surprise the monkey with food, the electrodes will record a transient flurry of activity among the neurons responsible for releasing dopamine. Dopamine is a darling of pop-sci discourse, commonly described as a pleasure molecule, but it is more accurately a significance molecule. It facilitates motivation, voluntary movement, goal orientation and pursuit, attention, memory, reward-related learning, and even hormone secretion. Its release is an indicator that something unexpected—something potentially important—has just happened.

Food is of perennial importance to animals, since they cannot make their own, so it’s no surprise a monkey’s brain releases dopamine when presented with food it wasn’t expecting. What is more interesting is what happens to this dopamine response when the food is made predictable by, say, a light that reliably flashes a few seconds prior to food presentation. Initially, the brain shows no substantial response to the light, but if the pairing is repeated over and over, the light will come to trigger the same dopamine release from the same neurons that the unexpected food once did, and—and this is really important—the food, now expected, will no longer trigger this dopamine release. It’s not just that the light has acquired significance to the monkey due to its association with food; there is a real and substantive sense in which the light has stolen the felt importance of the food. This is perhaps counterintuitive but on reflection makes ecological sense: If the food is reliably predicted by the light, then a monkey’s cognitive and motivational resources are more profitably spent trying to discover what, if anything, might predict the light, thus improving the overall effectiveness and efficiency with which the monkey can exploit its environment.

This shift in dopamine response from reward to reward-predictor is also seen in “operant” conditioning paradigms in which an animal learns to perform some sort of work in order to receive a reward. The bodily sensations associated with the work here function much like the light—i.e., as potential predictors of reward—and so if an animal is reliably rewarded for that work, the work will start to be experienced as rewarding in its own right, energetic costs notwithstanding. It may even become more rewarding than the original reward, as suggested by so-called “contrafreeloading” behavior, in which animals seem to reveal a preference for working for a reward (providing they’ve been rewarded for that work before) to obtaining the same reward for free.

We humans are not laboratory monkeys, but the “reward system”—which includes the midbrain neurons that release dopamine and the neurons in the basal ganglia, amygdala, and prefrontal cortex to which dopamine binds and exerts its effects—is highly conserved across all vertebrate taxa and functions remarkably similarly. But is there any direct experimental evidence that the learning of a reward cue devalues, in some sense, the reward it predicts for humans? Yes. De Houwer, and Baeyens (2000), for example, found that subjective ratings of a positively valent “unconditioned stimulus” (US) tended to decrease after pairing with a formerly neutral “conditioned stimulus” (CS), while the CS acquired a positive valence due to its association with the US. This US devaluation effect was replicated by Meirop, et al. (2019) (but only for positively valent USs). They also found that repeated presentations of the US alone were sufficient for devaluation, suggesting it is caused by habituation to a stimulus that has become predictable. Consistent with this, many studies on both humans and non-human animals have found that operantly conditioned behaviors that have become habitual persist with the same vigor even when the original reward is omitted or artificially devalued. Finally, contrafreeloading has also been observed in humans, and has been studied for decades under the (admittedly less cool) name “learned industriousness.”

This transfer of significance is also evident in the realm of sexual paraphilias, wherein the acquisition of an intense sexual fetish devalues—sometimes to the point of making impossible—sexual pleasure and release in the fetishized object’s absence. This term “fetish,” of course, has an older and more general meaning. In colonial and post-colonial Western Africa it denoted a physical object imbued with great metaphysical significance. It was, of course, viewed contemptuously by the majority of its European chroniclers and their audiences, in keeping with the general prohibition of idolatry in Christianity (let us pass over this irony for the time being), though some astute researchers, like Charles de Brosses, recognized the generality of fetishism and even saw in it the foundations of all religious thought and practice. The concept would go on to figure prominently in the writings of Marx, who held that the market value of a commodity obscured (in a way roughly analogous to how we’ve been using the term “devalued”) the value of the labor and relations of production that brought it forth. This is an imperfect analogy, since the valuers of the labor (viz., the laborers) and the valuers of the commodity (consumers, or the “market” as a whole) are not coextensive, but it still captures the broad sense in which fetishization leads to blindness toward a fetish’s original source of value.

In the business world a version of this phenomenon, whereby a metric aimed at measuring progress toward some target ends up effectively replacing that target, is known as “surrogation.” It is the sort of thing Campbell’s Law and Goodhart’s Law are meant to caution us against. I want to stress the generality and automaticity of this process. Fetishization is just what brains tend to do whenever something becomes strongly associated with something else they already find significant. It underlies all map-territory confusions, all instances in which a means to an end becomes an end in itself.

Though we have been talking only about rewards so far, the same holds for significant things of negative valence, and the resulting fetish may accordingly become an object of either adoration or aversion. In psychology, the term “phobia,” denotes a particular kind of negative fetish—viz., one imbued with the fear of a particularly unpleasant experience. In sociopolitical discourse, on the other hand, “phobia”—usually appended as a suffix (as in “homophobia”)—points to a much broader range of negative attitudes, from fear to anger to disgust to contempt. This latter, more general sense of “phobia” is much closer to what I have in mind, but because the term has by now a fairly strong partisan connotation, I will avoid it in favor of the more neutral “negative fetish” going forward.

One very general implication of all the above that bears special emphasis is that reward processing in the human brain is largely insensitive to reward type. The same dopamine neurons that respond to unexpected food can be conditioned to respond similarly to anything sufficiently strongly associated with food. And likewise for cues associated with other unconditioned rewards (or punishments). This is perhaps counterintuitive; it is natural to think—say, for evolutionary reasons—that simple sensory rewards relevant to survival and reproductive success must be processed differently than the more abstract rewards associated with, e.g., social affiliation, aesthetic appreciation, or moral validation, thereby maintaining a tidy division of labor (taken for granted in wide swaths of the social sciences) between “biological” and “social” motivation. But study after study after study has found that the human brain processes all rewards in a neural “common currency.”

It may be useful to think of motivated behaviors—whether directed toward an unconditioned stimulus or a fetish—in terms of games. A hungry monkey has an objective—find and consume food—and receives continuous feedback from the environment to help keep him oriented and progressing toward that objective. When he learns that a light reliably predicts food, his objective duly changes, and so too does the sort of environmental feedback that is meaningful to him. This is just what that shift in dopamine response brings about. It engages the monkey in a new, superseding game with new conditions of success and failure that trump the old in felt importance. We will return periodically to this game-centric perspective throughout the discussion to follow.

‘Dis Curse on the Discourse

Fetishism, facilitated by social media algorithms and the 24-hour news cycle, has played and continues to play an enormous role in the degradation of political discourse and the resurgence of adversarial populism in the U.S. and elsewhere. Its consequences have been, in a word, disastrous. It has fueled rampant hyper-partisanship of both positive and, increasingly, negative varieties; has driven bizarre political realignments toward policy platforms and belief systems that are increasingly hodgepodge, “vibes-based,” volatile, and philosophically incoherent; has normalized a cult-like attachment to bombastic leaders and influencers hawking oversimplistic solutions to complex problems (as often as not of their own fabrication); has fed a metastasis of naked political grifting throughout the commentariat and even among elected officials themselves; has made political hypocrisy the norm rather than the shameful exception; has conditioned us to to view all news, however brutely factual and neutrally presented, first and foremost in terms of its utility to us or our enemies, driving an unprecedented demand for misinformation, conspiracy theories, and copium; has reduced our fellow exiles in sentience to little more than tools to wield or obstacles to demolish in furtherance of myopic rhetorical games; and has generally eroded our interest in values, principles, and substantive policy and hypnotized us with an ever-evolving menagerie of obnoxious characters, reactionary ideologies, and shallow tribal signifiers.

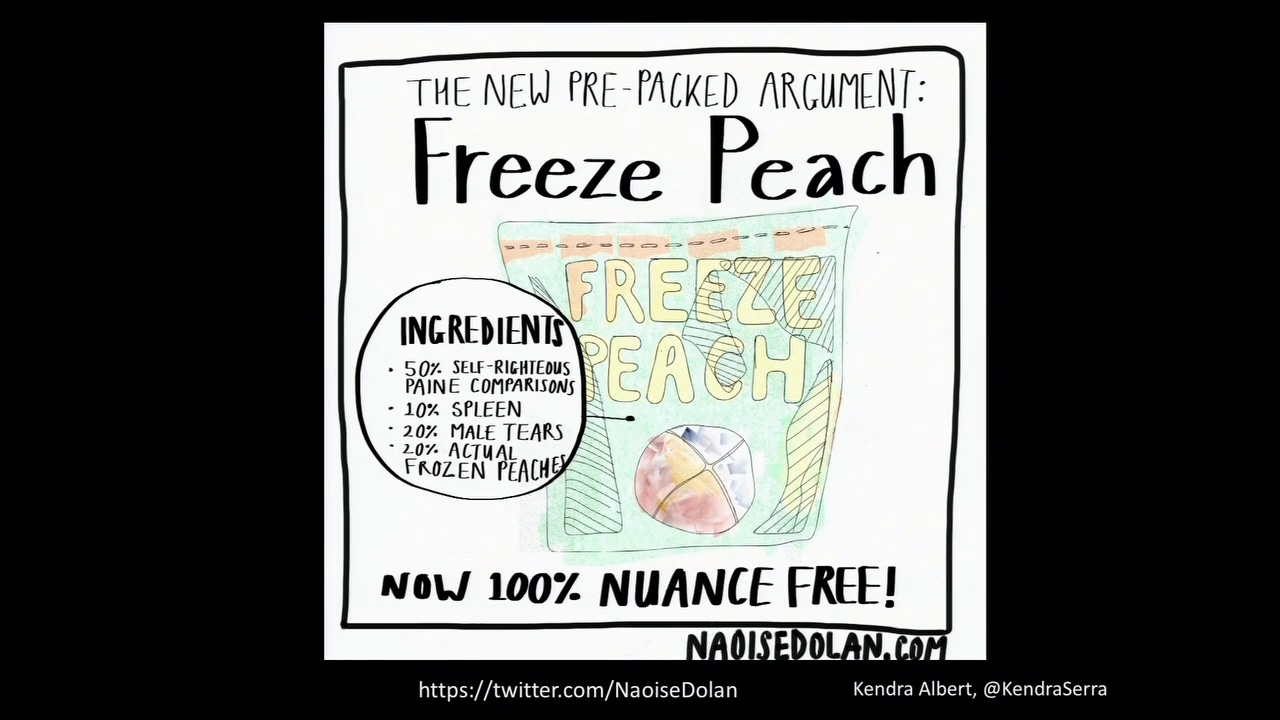

Political fetishes can be parties, narratives, slogans, symbols, and even individual words or phrases. Note, for example, how readily you can identify the political valence of the following: “equity,” “free speech,” “democracy,” “justice,” “family,” “elite,” “fact check,” “empathy,” “hierarchy,” and even “social” and “individual”.

Even my use of “discourse,” I suspect, is going to “code” me a certain way in the eyes of many readers.

Probably the most potent political fetishes, however, are people. The archetypal example here is the charismatic leader, but other figures—from pundits to public intellectuals or “sensemakers” to podcasters or other online content-creators—are also prime fodder for fetishization, whether positive or negative.

A candidate for office may become a political fetish for relatively straightforward reasons to do with his campaign promises and subsequent performance, but the pleasurable associations required for fetishization can also be created in a number of other ways: e.g., by echoing and validating people’s concerns, by excoriating or threatening their perceived enemies (pre-existing negative fetishes), or simply by amusing people in some way, shape, or form. Those who can provide these services in unexpected ways are particularly prime candidates for fetishization because, you’ll recall, dopamine release is highly predicated on surprise.

Case in point: You may have observed liberal critics of Trump at frequent pains to point out his background as a celebrity and wealthy coastal elite—the very thing his supporters purport to hate!—as if this were something the MAGA movement had simply failed to notice. This “criticism” betrays a failure to understand, among other things, how the brain’s reward system works. Trump is so beloved by his base in large part because he’s a coastal elite, an apostate insider eager to validate their outsider animosity. They do not expect validation from someone like Trump, so when they get it it is disproportionately significant to them. For similar reasons, people who despise academics love Jordan Peterson and Bret Weinstein and skeptics of systemic racism have a special affinity for Thomas Sowell. But this isn’t just a conservative phenomenon; the same unexpected validation effect has undoubtedly contributed to Democratic enthusiasm for vice presidential candidate Tim Walz, whose progressive positions are made all the more salient by his much more conservative-coded background (older white male veteran former football coach). We’ve seen it also, time and time again, in “resistance” liberals’ embrace of any Bush-era neocon willing to burn Trump on the record (more on this particular topic shortly).

When a person or other political object becomes a fetish, it enjoins its fetishists to a novel game in which the overarching objective is to see the fetish succeed against its rivals in political, cultural, or discursive space. “Succeed” here should be given a broad reading, inclusive of everything from real electoral and policy victories to general acclaim and social esteem to rhetorical “points” scored in social media skirmishes. This last type bears belaboring, counterintuitive as it is. We all understand politicians on the campaign trail are out to score political points in hopes their media teams will be able to parlay them into tangible electoral success. But what about all those rank-and-file randos—not the swarms of bots, but real people—with no appreciable reach and thus no realistic hope of influencing election outcomes? Why do so many of them seem every bit as invested in political point-scoring as the campaign’s loudest and most remunerated bulldogs and spin doctors? Their very vocal presence is such a commonplace of online life it’s worth a moment’s pause to register how strange it truly is. Fortunately, we now have the conceptual resources to dispel the mystery: The political points alone are sufficient reward for this behavior. Arguing on behalf of one’s fetish is reinforcing in itself, irrespective of ultimate impact because fetish-addled brains trading in a common currency of value cannot easily distinguish trivial from tangible accomplishments or symbolic from concrete victories. It’s all just so much positive feedback in the fetish-advancement game.

If this all sounds a bit like parasociality, that’s because it is—at least when the fetishes in question are people. But it’s important to remember the underlying mechanism is a highly general one. There is nothing inherently “social,” in the usual sense of the word, about this phenomenon; these sorts of one-sided “relationships” can be formed with just about anything.

Beliefs, for example, are common fetishes, and in this realization we have an explanation for the recent renaissance of absurdities like Flat Earth “Theory.” These sorts of beliefs, as many have correctly observed, are not approached and adopted out of a genuine concern for truth. They draw people in for other, pre-rational reasons—e.g., because they are invitations into a passionate and tight-knit community or because they license their proponents to fancy themselves uniquely knowledgeable and superior to the brainwashed masses or because they buttress a general distrust in experts who threaten other, already important beliefs or simply because they are amusing. Perhaps their adherents espoused them first in irony but enjoyed the rise this got out of people who weren’t in on the joke. Perhaps it felt good to have that kind of power over others’ emotions. Whatever particular form the initial enjoyment brought about by championing these beliefs, the dopamine produced thereby attached those positive feelings directly to the beliefs themselves, and the proponent was very shortly invested—unironically—in their cultural and discursive success.

This sort of non-epistemic investment in beliefs is not limited to the intellectual fringe either. One of Christianity’s most passionate and high-profile contemporary champions is Jordan Peterson—this despite the fact he does not himself identify as a Christian and turns reliably cagey and evasive when queried about his beliefs re: the existence of God or core Christian doctrines. It is perhaps more appropriate to say he is an ardent fan of Christianity. He vibes with it, is moved by its stories, and, perhaps most importantly, shares a large number of its perceived enemies. While he will not commit himself to its literal truth, he will invent sophisticated (or sophistical) ad hoc notions of truth in attempt to shore up the rationality of the true faithful. He has at times even redefined God as “the highest value in the hierarchy of values,” in order to fund the claim that everyone necessarily worships “God” in some form or other. Checkmate, atheists! These feats of conceptual re-engineering are precisely the sorts of rhetorical moves one sees when truth (in its plain meaning) takes a back seat to victory in a fetish-promotion game. That is to say, they are tools built primarily for point-scoring. The success of “God” in Western culture is more important to Peterson than how and to what the term actually refers.

Or consider ex-New Atheist Ayaan Hirsi Ali, whose recent conversion to Christianity had, by her own account of it, nothing to do with the assessed truth of any of the faith’s core tenets, historical claims, or metaphysical posits, and nearly everything to do with its perceived usefulness for combating the spread and influence of Islam, Ali’s most salient negative fetish. As New Atheism faded from public consciousness over the years and Ali’s cultural milieu became less generally secular (she emigrated from the Netherlands to the U.S. in 2006), Christianity emerged as Islam’s most obvious foil and capable opponent. Its antagonism toward the progressives who regularly accused Ali and fellow New Atheists of Islamophobia was certainly no small feather in its cap as well. Ali had built her public image defending cool rationality in the face of often barbaric religious zealotry, and her own quasi-religious turn is a poignant illustration of how quickly and thoroughly one’s rational faculties, however well-cultivated, can be captured and turned toward the business of rationalization on behalf of a powerful fetish.

I want to suggest here that fetishization is simply the elective component of personal identity construction. There is a real and important sense in which reward conditioning hijacks our hedonic and motivational circuitry, pressing them into the service of the persons, groups, or ideas with which those rewards have been subjectively associated. By this mechanism, our fetishes collectively become a sort of extended self, and we come to respond to their fortunes as if they were our own, reveling in their successes, and suffering—and I mean genuinely suffering—for their failures. This might have been adaptive in hunter-gatherer times in which the most prevalent reward predictors would have been our loved ones or hunting partners or preferred foraging sites or favored tools, but now, thanks to the associative thunderdome that is the Internet, it has us frequently serving ends that may have only the most tenuous, accidental connections to our own welfare and antecedent values, as we’ll see in detail the next section.

Before diving in, though, three final preliminary points:

(1.) Many of the behaviors to be described below admit of alternative explanations adverting to, e.g., social signaling, status jockeying, or simple, cold Machiavellianism. I want to suggest that these are pseudo-explanations, too suffused with post hoc rationalization to be useful for our purposes. They are how we make sense of our political behavior in a way that largely preserves our image as an essentially rational organism. They are more akin to reasons than to causes. Reasons are important in discourse, to be sure, but their true function is justification. True explanation, on the other hand, requires causes, and political behavior, like all voluntary behavior, has its proximate causes in the brain’s attentional and motivational circuits and whatever quirks they’ve developed during their evolutionary and individual reward learning histories. It is explanation, and thus causes, that we are concerned with here.

(2.) The monkey example by which the core dynamic of fetishization was introduced used food as the original (and subsequently devalued) reward, but there is an important respect in which devalued political rewards are unlike food. See, food is an unconditioned reward, a so-called “primary reward,” something the body needs to survive. Its value at any given time is determined not just by an organism’s reward learning history but by a brain structure called the hypothalamus, one of the body’s key homeostats. One of the hypothalamus’s most important functions is the maintaining of the body’s nutrient balance. To this end, it receives signals from various organ systems about their current states and in turn sends signals to the reward system to up- or down-regulate our motivation to pursue certain nutritive and other primary rewards (this is how, for example, we come to crave foods rich in simple carbohydrates when our blood sugar is low). This internal reward modulation system makes it hard to devalue food completely and consistently (though this may be achieved in extreme cases—e.g., severe anorexia nervosa).

In the relatively comfortable modern West, the things we sacrifice to our fetishes tend not to be unconditioned rewards like food, water, or shelter, but conditioned rewards like money, positive attention, moral vindication, aesthetic appreciation, and pre-existing fetishes. Unlike in the case of food, there are no visceral feedback systems for rewards like these and thus no way of independently re-upregulating their value after conditioning has rendered them predictable. I suspect therefore, that reward devaluation is even more dramatic and difficult to reverse in the political arena.

(3.) Finally, I want to clarify what I think are the proper uses of an analysis like the one offered in this post. I do not intend this model to be a tool for dismissing the claims of one’s political rivals via some sort of genealogical debunking argument—e.g., “Oh, you only believe that because you’ve fetishized X and lost yourself in the game of promoting X at all costs,” etc. Even where this is a true explanation, it is not an appropriate response to an argument. Again, reasons and causes have distinct discursive roles, and an argument is a demand for reasons. It is as wrong to respond to a demand for reasons with a causal deconstruction of the demander as it is to respond to a need for behavioral explanation with a list of justifications for that behavior.

But a behavioral explanation can and should lead us all to think more critically about our own political beliefs, as well as the incentives and enabling conditions that shape the discourse in which we participate. The previous paragraph notwithstanding, the fact is most fetishistic arguments are either bad or irrelevant—aimed as they ultimately are not at tangibly improving the world (by whatever metric) but at scoring points in some rhetorical game or other. It behooves us to know where this goal has become the norm so that we may re-allocate our time and attention more productively. And it really behooves us to understand what we may be giving up—perhaps irretrievably—when giving ourselves over to a fetish.

Fetishistic Derangement: A Modern Parable

The devaluation of the reward with which a fetish was at one time associated is one of the most tragic consequences of political fetishism. For remember: Every new fetish renders its associated reward more predictable, and thus less interesting, to us (as measured by reduced dopamine response). Over many iterations—for a fetish can beget new fetishes via the same basic reward conditioning process, passing significance down the chain ad infinitum—one can end up directly opposed to what were once highly valued and deeply felt convictions.

Consider a young man, the youngest child in a large family. We’ll call him Walt Cleft. Years of fighting with siblings and petitioning his parents for his fair due instilled in Walt a keen appreciation for equality and a visceral intolerance of oppression in all its ugly forms. Walt carries these values with him through childhood and adolescence, sticking up for victims, standing up to bullies. Later, he gets involved in charity work. He volunteers at shelters for the unhoused. At college he reads Marx and suddenly he’s got a theory to structure and justify and unify his values. Under Marx’s theory he comes to see class warfare as the ur-struggle and capitalism as the black well whence all forms of oppression spring. He begins to identify proudly as a socialist. Had he stayed in academia, he might well happily spend his entire professional life playing the largely inconsequential game of promoting Marxian analysis against its rivals in a literature that, by and large, only academics read, but he doesn’t want to confine himself to the ivory tower. He doesn’t want to be inconsequential. He involves himself in politics, first locally, then at the county level, then with the state. He starts a blog, a newsletter, a podcast. He spends a lot of time engaging others online, trying to rally the workers of the world.

On witnessing the emergence of the social justice movement, Walt is…a bit confused and concerned. He sees people from different minority groups fighting each other for the spotlight, competing in the “Oppression Olympics,” and making enemies of would-be comrades among the white working class and each other, and this all just seems to Walt like a wasteful and tragic distraction. Don’t they see that there can be no true liberation until the means of production rest again in laborers’ hands? Don’t they see that class identity is what really matters?

As social justice issues begin to dominate political discourse, he gives most of them a wide berth. He keeps his head down and sticks to his own hobbyhorses. He is heartened by the surprising popularity of Bernie Sanders and then shortly horrified to see almost the entire Democratic Establishment calcify in opposition to him. He watches the campaigns of Hillary Clinton and Elizabeth Warren and their supporters cynically accuse Sanders and his supporters—supporters like Walt—of sexism and racism. He observes the christening and wide circulation of the mean-spirited “Bernie Bro” meme. And all the while, he’s watching Corporate America, Hollywood, and even the fucking Pentagon start to leverage DEI and other “woke” fetishes for painfully obvious reputation-laundering purposes. He is furious. He wants revenge, and this desire consumes increasingly large amounts of his political energy. He rationalizes this pivot by claiming “wokeness” is the single greatest impediment to class consciousness and solidarity. That it is a psy op by the ruling class designed to keep the working class divided against itself, perpetually fighting each other for scraps (media representation, bespoke holidays, affirmative action initiatives) from the master’s table.

Soon, Walt is seeing the insidious hand of wokeness everywhere. In his employer’s HR policies. In the “forced representation” oozing out of every movie, TV show, and commercial. It gets to where he can’t even see a minority in real life in a position of power and influence without reflexively wondering whether they only got that job to meet a quota and help polish some ghoulish corporation’s public image. This is more than mere annoyance. Every instance of wokeness shoved in Walt’s face is a reminder of the failure of proletarian unity. A reminder that the forces of division are winning. A reminder of the betrayal of so many coulda-been comrades.

But in his rage Walt finds a new and unexpected solidarity—not with other members of the proletariat, but with comparatively wealthy conservative culture warriors, who’ve aligned against wokeness for their own, rather different, reasons. He guests on their podcasts. They guest on his. Their audiences adore him because, given his background, his validation of their grievances is a delightful surprise to them. Because he moralizes their anger—never mind how different his ostensible morals are from their own. They reward him for this service with views, subscriptions, and Patreon donations. Under their constant reinforcement, he grows ever more radical (a phenomenon known as “audience capture”). He endorses, promotes, maybe even gives fluffy interviews to right-wing strongman candidates who’ve made the demise of wokeness a top agenda item. Never mind that these candidates are not egalitarians in any sense. Never mind that they explicitly hold hierarchies to be natural and just and believe the country ought to be run like one of those ghoulish corporations Walt once held in such disdain with the president given the near-unilateral authority of a CEO, sans Board oversight. None of this matters to Walt, for wokeness has replaced inequality as Walt’s most salient enemy, and he is now all in on the game of ending it by any means necessary. A series of fetishizations—Marx, then Bernie, then wokeness (in the negative), then the avowed enemies of wokeness—has put Walt into direct conflict with the values and principles that drew him into politics in the first place.

In light of this dramatic realignment, it’s fair to ask: Does Walt actually care about equality anymore? If pressed to list his values on paper, he might well still put it at the top. And he will no doubt insist his new alliance is purely strategic, still ultimately in equality’s service. But this simply isn’t how reward learning works in vertebrate brains, and Walt’s focus and actions will constantly betray the fact that equality simply doesn’t motivate him much anymore. He is in the intellectual equivalent of a sexless marriage with it. The passion is all gone. Perhaps most importantly, the attention is all gone. Equality has become, at most, a convenient valorizing gloss on what Walt now really cares about: empowering someone who has credibly pledged to vanquish wokeness.

The Deranger in Chief

Maybe you know someone like Walt. Or someone who’s made a similarly striking transition in the other political direction (say, a Louise Mensch-ian hyper-Russiagater). Walt is, of course, fictional, but timely real-world examples of the erosive effect of fetishes on pre-existing values aren’t exactly hard to find. I don’t want to dwell on Donald Trump too much in this essay for fear of over-activating readers’ own fetish-advancement or -opposition games, but the fact is the man is the single biggest catalyst of mass value betrayal (among both devotees and detractors) in recent American history. One simply cannot talk about political fetishism in a modern context and not discuss the Trump phenomenon.

“Trump Derangement Syndrome” (“TDS” for short) is a new iteration of Charles Krauthammer’s 2003 “Bush Derangement Syndrome” aimed by Trump supporters at those they perceive as having been consumed to the point of irrationality by the need to criticize everything Trump says or does (or might say or might do). Though the term has been widely overused to dismiss any criticism of Trump, it has no shortage of legitimate exemplars. Alas, positive fetishization can hijack and distort rational faculties just as easily and dramatically as negative fetishization can (this is, of course, instrumental to the functioning of cults), and the reflexive use of TDS accusations is itself a telling symptom of this. Trump Derangement Syndrome is real enough, but it is a bipartisan affliction.

Among Trump’s supporters, the derangement and value drift of white evangelicals has been particularly remarkable. Excuse the perfunctory flogging of the obvious, but we are talking here about a twice-divorced casino mogul, a serial liar, fraudster, and adulterer, and a near-certain atheist. A man whose aspirations are wholly secular, material, and self-centered in nature. A man who embodies every single deadly sin to cartoonish degree while being constitutionally incapable of the humility required to acknowledge his imperfection and seek redemption in Christ. A man who demonized and put in serious physical peril his own vice president (someone with actual evangelical bona fides) for refusing to break the law and upend the American electoral process so his boss could illegitimately cling to power. Any premillennial pulp writer could pour the very same personality and power-hunger into her depiction of the Antichrist and nary an eyebrow would rise.

(Stow the TDS accusations; we’ll get to the detractors in a moment!)

What’s going on? Undoubtedly, the unexpected validation effect accounts for some of this zeal, but Trump doesn’t pander to evangelicals as reliably as he does other constituencies (mind, their devotion was cemented when Project 2025 was no more than a twinkle in The Heritage Foundation’s eye). No, the crucial factor here seems, once again, to be the sharing of enemies and animosities. Fact is, many American evangelicals, having committed themselves years or even decades ago to a bitter Culture War they have been slowly but decisively losing, had effectively abandoned many of the core values of their faith long before their golden calf descended his golden escalator. His values, or lack thereof, pose no issue because their own had long ago been lost in the fog of battle. Like Walt, they were already in thrall to powerful negative fetishes and were thus especially vulnerable to anyone who could convince them he was willing and able to destroy their enemies. Trump, in promising evangelicals victory in the Culture War, the game on which they had wagered nearly everything once of value to them, became a conditioned reward and thereby the architect of a new struggle in which his own victory is now the overriding objective.

But Trump is an equally potent negative fetish (it is nearly impossible to have a neutral opinion of the man), and one can see a similar degree of value drift among his detractors as well. Witness the galling number of erstwhile critics of neoconservatives’ disastrous “War on Terror” now scaremongering and saber-rattling daily about Russia due in large part to Trump’s numerous associations therewith (a pattern established well before the invasion of Ukraine and which is largely responsible for the polarization on that particular issue). Or note the ill-concealed giddiness with which so-called liberal media outlets now lionize any old-guard Republican hawk willing to criticize Trump for his (admittedly fickle and highly selective) dovishness. I suspect most of these ex-peaceniks don’t really want war with Russia or North Korea, but this concern is of evidently lesser importance now than seeing Trump dragged for his unwillingness to stand up to foreign dictators—a doubly delicious turnabout given (1.) how much Trump cares about personally projecting strength, and (2.) the amount of Republican flak Obama (no small fetish in his own time) received for being “weak on foreign policy.” For many, there may even be an element of personal vendetta involved. Critics of the Iraq War were branded “traitors” for years before the tide of public opinion finally turned, and some now seem to be relishing the opportunity to finally lord the mantle of patriotism over their political rivals.

This kind of realignment isn’t just a product of acting on the marching orders of Trump or his enemies. A fetishize-able object almost always comes to us embedded in a web of pre-existing associative connections, and so the reward associations we make with that object extend outward to these other things in its conceptual orbit, coloring or contaminating them with our feelings about the fetish—a phenomenon psychologist Eva Walther has dubbed “the spreading attitude effect.” Those who really commit to Trump-promotion or -opposition games are, whether they know it at the time or not, signing up for a whole slew of attitudes and beliefs directed toward not-otherwise-obviously-connected things like masks, tariffs, NATO, mail-in voting, immigrants, Facebook, Bitcoin, Elon Musk, Anthony Fauci, Vladimir Putin, and Volodymyr Zelenskyy, among many, many others. Some partisans, of course, will have had strong pre-existing opinions on one or more of these topics and will have been guided toward or away from Trump on that basis, but the deeper into their respective Trump-centric games they are pulled, the more vulnerable they become to having the rest of their opinions shaped by the hodgepodge of battle lines Trump has drawn. A political fetish is rarely adopted in a one-and-done manner (particularly in today’s saturated media environment, which facilitates rapid and robust reward associations); sooner or later its friends and enemies become part of the deal.

Changes can ripple through these webs of association with alarming speed. Trump’s own opinions—at least where they do not concern his own greatness, the wickedness of his enemies, or the illegitimacy of every happening not to his benefit—are famously unstable, and one may witness dramatic reshufflings of apparent values, beliefs, and priorities among both supporters and critics in real time as his thinking shifts on various issues. When, for example, he threatens Iran with war (and war crimes), or proposes bombing and invading Mexico, global peace suddenly becomes a top priority among his liberal critics once more, while the MAGA faithful reliably reveal they have rather more appetite for military conflict then their particular pacifism toward Russia had suggested.

Though it’s hard to prove in any specific case, given the inexhaustible creativity with which we can rationalize even our most arational impulses, it sure as hell looks like a great many Americans’ current attitudes toward war have a lot more to do with their feelings about Trump and whom he, for his own personal and financial reasons, has designated allies and enemies than it does any deep moral principles or relevant geopolitical particulars. The more people have become engrossed in the game of promoting or opposing Trump, the less attention they seem to have for erstwhile games like maintaining strategic international alliances or avoiding nuclear apocalypse. This is the kind of political tunnel vision fetishism inflicts on us. A sufficiently potent political fetish warps discourse and policy around itself like a black hole distorting spacetime. It becomes the lens through which all associated issues are viewed, its success or failure a litmus test for all auxiliary opinion. And lest you think our fetishes themselves are merely orchestrating this process from a safe intellectual distance, let us not forget just how much Trump’s own 1st term policy agenda was dictated by his obsessive negative fetishization of Obama.

Signs, Symptoms, and Side Effects

The kind of bipartisan hypocrisy orbiting the Trump phenomenon is but one of a number of telltale indicators of a commentariat and electorate plagued by fetishism. A conspicuous fact about the current state of political discourse is that accusations of hypocrisy are both omnipresent and completely ineffectual at changing beliefs or behavior. They are ineffectual because those accused feel little to no actual cognitive dissonance, since the values they are contravening in furtherance of their fetishes have long gone motivationally inert for them. The accusations are omnipresent because, despite their ineffectiveness, they still make for good zingers. That is to say they are useful for scoring political points and reinforcing existing negative attitudes, and thus are rewarding irrespective of their impact on targets’ behavior.

Unheeded tensions can arise not only between a fetishist’s current objective and prior values but between claims and apparent beliefs about the very same objects, persons, facts, or events—a phenomenon not dissimilar to Orwell’s “doublethink.” This happens because those in the grip of a powerful fetish start to view everything else in terms of its potential contribution to the fetish’s success or failure. Proclamations about non-fetish things become mere tools to be leveraged when useful and discarded as soon as another would better serve the fetish’s interest. That the tools may say or imply contradictory things is far less important than that they confirm our feelings about the persons, institutions, or ideologies involved.

Case in point: If you’ve been party to enough online COVID-19 debates you may have noticed that the claimed severity of SARS-CoV-2 (is it a deadly bioweapon or no more serious than the flu?) seems to depend a lot on whether the focal topic is the pandemic’s murky origins or the justifiability of lockdowns and mask or vaccine mandates. Inconsistencies like this would be important if these debates were truly about the object-level arguments, but they—increasingly—aren’t. Nor are they about the lessons we could apply to help avoid or better respond to future pandemics (we can come to sensible conclusions about the risks of gain-of-function research and exotic animal farming regardless of which practice happened to have released this particular virus upon the world). No, these debates are by this point primarily about who among the relevant public fetishes—Trump or Fauci, Joe Rogan or the MSM, DRASTIC or the professional virological establishment—was right and who was wrong. Who lied and who stood up for truth against a tide of cynical opposition. The animating aim of most combatants here is simply to see their heroes vindicated and, perhaps even more importantly, their enemies exposed for the liars and devils the spreading attitude effect requires them to be. The ever-widening appeal of conspiracy theories—whether about COVID-19 or anything else—has much less to do with the plausibility or coherence of their details than with the fact that they cast the heroes, villains, and victims appropriately. Their fetish-congruence is the only sniff test that matters.

Another reliable indicator of rampant fetishism is a reflexive “with us or against us” mentality situated obviously around the fetish in question. If Alice and Bob share numerous values, principles, issue-and-policy-level beliefs, and even party affiliation, but disagree about a particular candidate and treat each other as mortal enemies over this fact, then that candidate is a clear fetish—positive for one disputant; negative for the other. The inverse is also seen: If Walt and his fellow anti-woke crusaders come to think of each other as comrades, despite the polar opposition of their antecedent moral and political principles, it is because their shared enemy has sapped all meaning from those principles, trivializing them to the point that disagreement over them doesn’t much matter anymore. Walt and co. are no longer playing the game of advancing their respective principles; they are playing the game of halting the advance of wokeness.

In general, to find someone’s political fetishes, look for the conflicts consistently foregrounded in their psychology. The ones they can’t stop bringing up in conversation. The ones about which they are always looking to score points.

Relatedly, witness the ubiquity of knee-jerk “whataboutism.” Visit the comments under any article, video, or social media post reporting on a fact inconvenient for a particular fetishized political team or figure and you’ll see aggrieved partisans clamoring for equal or greater coverage of facts inconvenient to their rivals. In the three weeks between Joe Biden’s disastrous performance in the first 2024 presidential debate and his withdrawal from the race, any mention of his obvious age-related cognitive decline was reliably met with indignant references to Trump’s latest on-air ramble or Truth Social meltdown. On the other side, express concern over Trump’s attempted coup (yes, it was an attempted coup, of which the events of January 6 were only a small part) and you’ll be immediately and indignantly redirected toward the BLM riots or the DNC’s “coronation” of Kamala Harris following Biden’s exit. This type of response is not, by and large, intended to justify the behavior originally being criticized. Nor is it merely another of those commonplace accusations of hypocrisy (it is that, but not only that). Rather, it is a personal demand—to you, the news organization, or the universe at large—for emotional restitution. Its function is psychic triage, the stanching of a painful rhetorical loss and rebalancing of the moral scales. In drawing attention to an inarguable failing on the part of their fetish, you have wounded these people, and fairness dictates you and your team take one on the chin in return.

Political fetishism has altered how we interact with information profoundly. Every fact, however dry, is now tirelessly inspected and dissected for its rhetorical utility against our negative fetishes. Observe, if you dare, social media in the wake of any mass shooting or other high-profile violent incident and witness the droves of fetishists—pundits and rank-and-file partisans alike—scrambling madly for any evidence they can use to blame their rivals for it. If such evidence is not readily forthcoming, they will speculate it into existence or outright fabricate it. If the perpetrator starts to look like a member of their own team, they will cry “false flag” or pivot to a different hobbyhorse to which the current context is more favorable (“the real problem is inadequate gun control/the decline of Judeo-Christian values!”). They may even resort to mealy-mouthed rationalization: “Well, I don’t condone what they did, but it’s understandable why they felt they had to do it, and that should really tell you something about [negative fetish] and what [he/she/it] has done to the country…” (here again the blurring of the distinction between causes and reasons rears its head). They’ll decry the politicization of the tragedy and call for civility only when their own ammunition scavenger hunt has failed to turn up the goods. The incident in question needn’t even have an intentional origin. Industrial accidents too now reliably bring die-hard culture warriors out of the woodwork to blame, in pre-emption of any evidence, either greedy, corner-cutting CEOs or incompetent “DEI hires.” Even natural disasters are fair game, as Hurricanes Helene and Milton amply demonstrated. Everything is now grist for the fetish-promotion or -opposition mills. Everything is a pawn in a rhetorical game.

It is tempting to think this must all be the work of bot networks and nefarious foreign influence campaigns aimed at stoking domestic divisions. I don’t want to dismiss these explanations entirely—bots really are everywhere now, and will only grow in number and effectiveness as AI technology advances—but I’ve seen far too many verifiably real people gleefully participating in these post-tragedy feeding frenzies to believe the problem can be fixed by stricter content moderation or more robust fact-checking. I am much less concerned about the supply of misinformation, outrage bait, and biased news and sensemaking than I am the staggering demand for it.

This vulturistic approach to tragedy runs roughshod over basic human empathy, and this is perhaps its darkest consequence. The tunnel vision that develops around the rhetorical games in which fetishists become engrossed blunts in importance anything not clearly game-relevant and villainizes anything that stands to hinder success—be they negative partisans actively invested in the failure of one’s fetish or merely anyone said partisans could conceivably use for critical ammunition—including innocent casualties and those who report on them. What does the fetishist’s response to such unwitting bearers of bad news look like? It looks like Alex Jones accusing the child survivors of school shootings of being “paid actors.” It looks like a certain strain of terminally online feminist mocking lonely young men for falling behind. It looks like the unvarnished contempt the rich have for the poor, the fear and disgust the comfortably housed have for the unhoused, and the reflexive disregard the vast majority have at any one time for the plight of Native Americans or any others at home or abroad who suffer in effective silence in the shadow of America’s great success story.

When the game in which a fetishist is heavily invested seems to be resulting in unintended harm, his first impulse will be to hide this harm away. Where this is not possible, he may attempt to downplay the harm. Where this cannot be done convincingly, he may portray the harmed parties as secret collaborators of his opponents. Finally, should all the previous attempts to defang this inconvenient fact fail, he may simply resort to blaming the victims for their own suffering. His fetish, after all, is an instrument of perfect justice, and so those harmed by it must have been, somehow, deserving. The sad fact is that for many it is cognitively easier to demonize innocents than to critically reevaluate one’s fetishes. In instrumentalizing everyone in terms of their actual or potential impact on some totalizing rhetorical game, political fetishism becomes a potent force for dehumanization—and all the well-known moral horror to which it reliably throws open the gate.

And in instrumentalizing (mis/dis)information in similar ways, facts and factuality are bled of their importance and capacity to constrain what we are willing to claim, argue for, and act on. We are, you might have heard, now in a post-truth political era. Much of the blame for this has been laid at the feet of Trump and his Tea Party predecessors, and not without reason, but the problem is, increasingly, a bipartisan one, as evidenced by the slew of progressive “BlueAnon” conspiracy theories following each of the recent Trump assassination attempts. This sort of thing used to be the province of a relatively small number of tinfoil-hatted eccentrics, but conspiracism today is simply one of a number of psychological coping mechanisms we deploy to avoid the honest processing of any potentially fetish-threatening information. In positing shady cabals of enemies behind every politically inconvenient fact, we can re-contextualize just about any apparent bad news into something less emotionally challenging to our fetish-related prejudices. Something that crucially preserves and protects our headcanon of heroes, villains, and victims.

Upset that the assassination attempts on Trump might make him seem more sympathetic—maybe even heroic—to undecided voters? Clearly, his team staged the event for just such purpose (I mean, come on, this is Trump we’re talking about), so you can at least take comfort in the fact that he won’t deserve any of that positive attention. And to the extent others see through the deception, it’ll only hurt him in the end.

Worried the devastation of yet another major hurricane is going to boost the credibility of those insufferable climate alarmists? Since it is as good as axiomatic to you that they can’t be right, the only sensible explanation is that they’re engineering these hurricanes using weather-manipulation technology and aiming them at Florida to aid the Harris/Walz campaign and brainwash more rubes into their radical communist agenda (yes, this is a thing people have actually claimed).

The hurricane episode is worth spending some time with, because it really brought to a dramatic crescendo so many of the nasty fetish-fueled tendencies discussed above. Loony as the weathermaking conspiracy theories were, the real scandal here is the demonization of FEMA workers as the full weight of the modern right-wing conspiracism ecosystem was brought down upon them. Why did this happen? The simple answer is that FEMA is an “alphabet agency” associated with the current (Biden) administration and Kamala Harris by extension and so must, according to Trump’s fetishists, have evil intent. Here again, I encourage you to resist the temptations of a strategic explanation for this. Right-wing media, of course, have tangible incentives to spin up these narratives in attempt to deny Harris any potential electoral bump from a successful disaster response, but the foot soldiers of this insanity are neither 5-D electioneers nor thoughtless dupes passively absorbing Fox News talking points. They hate—genuinely, non-cynically hate—FEMA because the game in which they’ve lost themselves requires anything positively associated with Biden or Harris to be the enemy. The conspiracy grifters and right-wing media are simply giving them ammunition and “rational” cover to give in fully to their animosity.

Indulge me in one final example, for it’s particularly telling: Following Trump’s poor performance in the second 2024 Presidential debate—the first between him and Harris—MAGAland was awash in the conspiracy theory that Harris had cheated by having the answers relayed to her through NOVA H1 Bluetooth earphones.

In the end, Harris’ earrings proved to be…just earrings: a pricy set of Tiffany pearls she’s worn for years. But let not the fetish-addled fret! Conspiracist extraordinaire and would-be Nobel laureate Bret Weinstein has worked out the real conspiracy here. As he explains on his Dark Horse podcast:

“…I think this is another trap. I do not believe that this was done with something like an earbud, nor do I think it could have been done. And so my guess for that was it was the earring or a facsimile of it used to cause everybody to go ‘I know how they did it! She had somebody talking in her ear, right?’ And I won’t be surprised if there’s some reveal there’s some other earring that this actually was that doesn’t do that or…I don’t know what it’s going to be, but…um…but anyway, again, traps abound. That’s the thing that I think people need to understand is that we are now being targeted in order to make us jump at things that aren’t real and that it’s important to resist that.”

This is an incredible illustration of the extent to which conspiracy theories are being used as political pacifiers. If your team ever gets embarrassed publicly falling for a provably false conspiracy narrative, simply posit an even more insidious conspiracy that had exactly this outcome as its objective. With the magic of paranoia, a little creativity, and the utter inability to sit with emotional discomfort for any period of time for any reason, your fetishes need never suffer legitimate defeat again. And the pain of taking any L will now always be leavened by the confirmation of the nefariousness of your enemies—a reward nearly as compelling as an unambiguous win. In the clown world into which rampant fetishism has ushered us all, conspiracism is the new (c)opium of the masses.

I earlier likened the effect of a powerful fetish on discursive space to that of a black hole on spacetime. This, in conjunction with the spreading attitude effect, can lead to rapid and dramatic polarization (though not necessarily along traditional left/right lines). One can get a sense of the extent to which these effects have distorted a particular discursive space by noting which views or combinations of views, though internally coherent and consistent with known facts, are nevertheless conspicuously rare. Take the war in Ukraine. Contrary to the gut feelings of most partisans, there is no contradiction between the following propositions:

(1.) Russia’s incursion is a morally unjustifiable assault on the right of the Ukrainian people to sovereignty and self-determination.

(2.) Any U.S. involvement in the conflict could only make a bad situation worse—whether due to the threat of nuclear escalation or simply our abysmal track record in military interventionism.

I am not recommending this particular combination of views to you; I only want you to note that it is, whatever the net pull of your feelings on this issue, perfectly coherent and yet hugely underrepresented among the Ukraine war commentariat. In practice, most who support Ukrainian sovereignty also strongly believe the U.S. must do something to help repel Russia’s forces and most who believe the U.S. needs to stay out of this conflict spend an awful amount of time attempting to rationalize Putin’s imperialism as a necessary response to the threat of NATO expansion (look for that perennial weasel word, “understandable,” wherever claims like this are made). Neither of these moves is a logically necessary extension of the original proposition.

There is, of course, a rather mundane explanation as to why holding a combination of views (1.) and (2.) above is unlikely to be popular: It’s simply unsatisfying to acknowledge a problem one isn’t in a good position to solve. But in the current climate around this issue, I think a much bigger factor is the simple psychological fact that adopting any perspective falling somewhere between the two party-line narratives is going to involve the considerable discomfort of conceding an important talking point to those who vehemently disagree with and dislike you. If you’re adamant about the moral wrongness of Putin’s invasion, then you may feel like something of a sellout joining with those who believe Putin is in the right and Ukraine is the real enemy in their calls for non-intervention. Conversely, if you are strongly committed to the U.S. staying out of the conflict, then you’re not going to want to weaken your case by granting the interventionists’ claim that Russia is the wrongful aggressor here.

Note how in this way polarization is self-reinforcing. The more I dislike my opponents, the more emotional friction I will feel agreeing with them on even the most trivial points. This incentivizes a kind of totalizing antagonism that just deepens the dislike and makes the friction of agreement that much more unbearable. In the context of such mutual hostility, agreement feels like submission. And in the attempts to avoid this feeling partisans often end up simply abandoning what might have been common ground to their rivals. When discourse becomes a battlefield, claims, concepts, and even individual words become conquerable territories. This is how such things become “right-” or “left-coded,” contaminated with our feelings about the persons, teams, or ideologies with which they’ve been (however contingently) associated. Radicalization is as much about what we give up as it is about what we newly adopt.

10 or so years ago, online conservatives rather loudly and insistently branded themselves defenders of “free speech”—to the extent that the term became for many progressives nothing more than a dogwhistle, a conditioned cue for negatively valent ideas about race, gender, and sexual orientation—something to provoke an immediate defensive or dismissive reaction.

At the time of this writing, “democracy” is undergoing a similar transformation, but now it is progressives who are positioning themselves as the concept’s sole champion, while conservatives are in retreat and burning the fields behind them.

I don’t know to what extent partisans of either team intended to turn their opponents against formerly bipartisan desiderata like free speech and democracy, but it is clear how a sufficiently polarizing and savvy figure could leverage the above dynamic to his political advantage. Want to get your rivals to radicalize themselves right out of the Overton Window? Simply style yourself a defender of a lot of noble common-ground concepts and regularly invoke them by name to ensure your enemies begin to associate them with the antagonistic feelings they have toward you. They will grow suspicious of those concepts in a very obvious way and eventually cease trying to claim them for their own team, effectively ceding that moral territory to you. Better still: tar your opponents relentlessly with a label beyond the common pale (“communist” and “fascist” are evergreen options here) and watch them slowly embrace it—first with sarcasm and mocking irony and then, little by little, with sincere defiant pride and “you-insist-I’m-an-x-so-I’ll-treat-you-as-an-x-would” hostility. To those so labeled, this development will feel like the wresting of a rhetorical cudgel out of a bully’s hands, but to bystanders it will look like the slipping of a mask. You will insist on the veracity of this impression, will claim your enemies have now outed themselves as the monsters you’d correctly pegged them as from the start, and they will have no satisfactory answer to this accusation because the truer story—that they have come to their extremism by reactively hating what their opponents profess to love and loving what their opponents profess to hate—would make them look even worse than evil. It would make them look childish.

But, dear reader, we are childish. The crude associative para-logic of affective contamination on which the child’s mind operates so transparently is not exorcised with puberty or elite education or the taking up of adult responsibilities. It is only papered over. The reason by which we purport to distinguish ourselves from the rest of the Kingdom Animalia more often than not only makes us shrewder servants. This mode of information processing is an inheritance going back to at least the Cambrian explosion. It served us well enough in the relatively simple sensory informational environments of our ancestors, helping us learn and exploit the often highly stable contingencies underlying pleasant and unpleasant experiences, but it is woefully inadequate for guiding us through constructive political exchange in a modern, post-industrial society.

If we’re to get any better at activities of the latter sort—and we must, we must—we will need to start understanding in an intimate, first-person manner the many ways our reward systems can be hijacked by blowhards and bullshitters and cheap identitarian paraphernalia. Much humility will be required for this, and if you’ve been reading along and silently back-patting yourself for having never so much as heard the siren song of these petty incentives, then I’m afraid you still have much work to do on this count. Again, we are not talking here about a bias that afflicts only the intellectually lazy or incautious; the learning process that gives rise to political fetishism is a core function of all normal vertebrate brains. Fancying oneself “centrist” or “politically homeless” or “free-thinking” confers no automatic immunity.

Get Yer Head Outta the Game

So, let us be honest: We all have political fetishes. I have mine and, unless you are completely disengaged, I’m confident you have yours. What does this mean for us? Firstly, it means that issues that plausibly bear on the success or failure, the rightness or wrongness, the justification or repudiation of our fetishes will be of exaggerated importance to us. Secondly, it means we will be pre-rationally disposed to accept claims or data that bear positively on our positive fetishes or negatively on our negative fetishes and pre-rationally disposed to reject claims or data that bear negatively on our positive fetishes or positively on our negative fetishes—even in seemingly trivial ways (to see this, try giving a minor, peripheral compliment to a political rival in the company of your co-partisans and observe how resistant some will be to granting even this completely irrelevant point).

Fetishization is not universally bad. It is, for one thing, how we fall in love; it sweeps us effortlessly from the enjoyment of particular things about a partner—their beauty, humor, kindness, or competence, etc.—to enjoyment of the partner holistically. True, this may mean those particularities become less important to us, but that is often a sacrifice worth making. And this, I think, points us toward a helpful question. It is probably not possible to wholly resist fetishization by sheer force of will, but if we become sufficiently mindful of the circumstances that facilitate fetishization and sufficiently attuned to what it feels like to be starting down that garden path, we can ask ourselves early in the process “is getting into this new thing worth giving up something I already care about?”

Because the giving up part truly seems non-negotiable. Every new fetish demands the sacrifice of something currently important to you. If you take nothing else away from this post, please understand that. So we need to think very carefully about the costs and prospective benefits of any given instance of fetishization. One thing that makes this difficult is that our engagement with fetishes (of any kind) often feels deeply, intensely meaningful. This is no surprise, since dopamine is what mediates this feeling, but the dynamics of reward learning tell us that any cue’s gain in dopaminergic capacity is the original reward’s loss. That is to say, when a political object becomes newly meaningful to us, something else must be getting plundered for that meaning.

So, to determine whether any prospective new fetish is worth it, we need to know where it would be stealing its meaning from. We need to ask ourselves what exactly it is about this person or tribe or ideology that is speaking to us so compellingly. Often, the answer will be along the lines of “they oppose the people we oppose,” in which case we will have to press further: What was the thing we wanted to fight these people over in the first place? Is it really worth sacrificing just for the prospect of a provisional, almost certainly ambiguous, and perhaps largely symbolic victory?

And here is where the rationalizations will come out. Here is where we’ll try to convince ourselves our fetish is nothing more than a means to a greater, nobler end. That it has only borrowed its meaning. That when the war is won, we’ll return with just as full a heart and undivided attention to the things that used to animate us and make our lives worth living. But will the war ever truly be won to our satisfaction? Can the enemies of an idea or movement or political figure ever be wholly converted or purged from our awareness? Was fascism itself sentenced to death at Nuremberg? Did communism vanish with the collapse of the Soviet Union? Or are their emissaries still about—lurking behind everything wrong in the world, threatening to corrupt each new generation?

Here’s the tricky thing: A perceived victory—be it legal, political, or cultural—often creates an expectation one will henceforth be largely free of the unpleasant experience of encountering one’s enemies or their views, and because dopamine is gated by surprise, the inevitable violations of this expectation enflame our animosities to staggering new degrees. The rarer our enemy’s presence becomes, the more intolerable it grows. The more covert our opponents, the more dangerous our complacency. Our war, in effect, never ends; we approach Armageddon only asymptotically, and as the grip on our metaphorical sword tightens, so too does the fetish’s grip on our minds.

To see this, reflect on what has happened to the fight against racism and sexism following the momentous victories for equality achieved in the U.S. in the 20th and early 21st centuries. The great struggle has not wound down; it persists, every bit as passionately, as the movement now widely derided as “wokeness,” a seemingly inexhaustible campaign against ever subtler and more insidious forms of bigotry and oppression. And as more and more bystanders who thought they were on the right sides of the original issues nevertheless found themselves being branded enemies for increasingly inscrutable reasons, a predictable backlash mounted that has now more or less re-ignited all the old battles, placing the futures of marriage equality, women’s rights, and even desegregation back on uncertain political footing. Should the anti-woke forces win this next round, the aftermath will be much the same, a tale of concept creep and pogroms and witch hunts that inevitably ushers in another cycle of open, often violent conflict.

So don’t count on being able to return from the Culture War to what once mattered (unless you’re willing to unplug from the culture completely). There will always be one further battle, one more enclave of resistance to rout. This isn’t to say there aren’t things genuinely worth fighting for in that arena, but you need to be honest about what actually animates you, moment to moment, about the causes you’ve taken up. Is it still the values and principles that (I’m charitably presuming) originally drew you to this struggle? Or is it the destruction of their opponents? Or the success of some figurehead in whom great hope has been placed? Really reflect on how these things make you feel; note how your heart rate responds, how the pace of your thoughts changes around them. Note what information captures your attention. Ask yourself of your movement’s leaders and celebrities “What would they have to do to make me feel seriously betrayed?” If your answers are mostly along the lines of “Not punching the enemy hard enough,” then I’ve got bad news about those values and principles...

Let’s say we’ve done the work and identified which prospective fetishes wouldn’t be worth their cost in pre-existing meaning. Will that knowledge alone be enough to protect us? Maybe not. Again, fetishization is something brains just tend to do naturally, so we may need to take active steps to hinder the process, like limiting our exposure to positive stories or memes about the would-be fetish. Touching grass more often is rarely a bad idea.

And what of those fetishes already acquired that, on reflection, we’d like to be rid of? This is a trickier matter still. Conditioned physiological responses, like the drooling of Pavlov’s dogs, tend to attenuate once the unconditioned stimulus ceases to follow the cue, a process known as extinction. But strong feelings that have attached to a conditioned stimulus/fetish are much more resistant to extinction (studies here, here, and here). What may be needed instead is what psychologists call counterconditioning, the pairing of the conditioned stimulus/fetish with new stimuli of the opposite valence—so, negative stimuli for a positive fetish or positive stimuli for a negative fetish.

Willingly subjecting ourselves to contrary information about a fetish, though, is going to involve enduring a lot of cognitive dissonance, and we must choose our oppositely-valent stimulus carefully. It needs to be something we have stronger feelings about than the fetish we’d like to demote or the conditioning may go in the wrong direction—that is, the fetish may alter how we feel about the new stimulus rather than the other way around. It may be difficult to find a sufficiently powerful stimulus if we’ve really invested ourselves deeply in the fetish. If, for example, we already care about Trump more than we care about democracy (not in the on-paper sense, but in the brutely neurophysiological sense), then exposing ourselves to information about the threat Trump poses to democracy is more likely to sour us on democracy than on Trump—a phenomenon we’re already starting to see on a large scale, as noted previously.

Should counterconditioning prove impracticable, another option for curbing a fetish’s influence on our thought is to simply try to minimize the amount of time said fetish is active for us. This will require us to avoid engaging with both positive and negative information about the fetish—a restriction that may significantly limit our participation in political discourse. This is a cost we’ll have to weigh against the costs of continuing to participate in a fetish-addled manner.

For my part, I’m very skeptical that any political fetish is worth the sacrifice it demands. Being a philosophy nerd, I have a set of (what I think are) fairly well thought-out moral values and ethical principles that I’ve worked my way toward in a largely pre-political way, and I’m loath to put them at hazard for any given politician, team, movement, or ideology. I don’t want to get stuck in a game in which opposing candidate X or promoting team Y monopolize my attention and energy to the exclusion of, e.g., reducing global suffering or mitigating existential risks. Of course, I didn’t come to my current realizations about the perils of fetishization until after I’d already acquired some political fetishes—both positive and negative—of my own. I’ve generally adopted a limit-exposure approach to trying to minimize their influence, but it isn’t easy to do this and stay well-informed. I think it much more preferable to avoid fetishization in the first place when- and wherever possible.

At this point it may be instructive to step back a moment and try to imagine how someone with well-developed principles would engage politically in a completely fetish-free way. The exercise paints a strikingly unusual picture in the current climate. Such a person wouldn’t be loyal to any one candidate or party. She would take all issues relevant to her values and principles into account in determining what to promote and whom to vote for. Specific circumstantial details would be crucial to her political decision-making. She would favor whatever she thought was the best option in the present situation, irrespective or who proposed it or how it was “coded.”

She wouldn’t even be loyal to a larger political ideology like liberalism, socialism, or libertarianism. And why should she be? Let’s exercise a little humility and admit just how surprising it really would be if any of the big marquee political -isms of our time proved decisively to be the best suited among all its rivals, known and unknown, for any society under any set of circumstances. What are the odds that the game of human flourishing has always and everywhere only a single political solution and that we—the smart and virtuous ones, that is—after only a few thousand years of highly contentious trial and error, have hit upon it?

More fetish-friendly acquaintances will probably consider her faithless, a flip-flopper, maybe even a cynical opportunist, but she is only trying to follow her principles as best she can in a messy and uncertain world. To the extent that others feel betrayed by this it is because they’ve so elevated their own parochial commitments they no longer know what truly principled behavior looks like.

A strange portrait, this—at least in the context of national politics. But our heroine’s behavior isn’t so different from the approach voters tend to adopt toward more local electoral matters. Partisanship is notably diminished at the local, city, and even state levels, with people showing far more willingness to vote across party lines or abandon previously supported candidates who fail to deliver on their promises. The common explanation for this is that the consequences of these elections are more tangible and direct, incentivizing both voters and campaigners toward greater pragmatism. But I don’t think this tells the whole story. National elections can have consequences every bit as impactful at the state, city, and local levels. What they have in addition that lower-level elections don’t, however, is 24/7 coverage on cable news and nigh-inescapable discussion on social media. We are inundated with national political information and are thereby given much more opportunity to form the kinds of reward associations of which fetishes are made. This underscores again how important our media diet is to the healthy functioning of our brains and, by extension, the quality of our civic participation.

I want to close with a final plea. In the last section, I wrote about some of the ways political fetishism harms society and its culture. But, of course, fetishization’s first victim is the fetishist himself. You probably have at least one person in your life who has succumbed to what we may call “terminal politics-brain.” The guy who always has to steer conversation toward his political complaints. Who always has to shoehorn irrelevant jabs at his enemies into every discussion. Who consumes partisan outrage bait like a drug. Whose behavior has perhaps even estranged him from friends and family members. His life to him feels full of meaning, but to any neutral outside observer, it is transparently sad. All that meaning has been pillaged from other sources, funneled into this narrow obsession that’s shrunk his world in exactly the way addictions do. Nothing else moves him now. It is not a life to envy and not a course easily reversed.

Most of us are neither perfectly fetish-free nor hopelessly fetish-addled, but we should endeavor where we can to be more like the former and less like the latter. Some amount of political fetishization is probably inevitable, but let us at least be honest with ourselves about what we stand to lose in that often Faustian bargain and take what measures we must to save what really matters when that cost would be too high.

For the sake of the world and our own souls, let us fetishize responsibly.

Great article. Really. You beautifully captured a lot of the current climate and potential consequences of it with ample illustrative examples. Following for more.